Today, I would like to take you on a journey to Minamata, located on the west coast of Kyushu in Japan. This place became synonymous with the devastating condition known as Minamata Disease, which caused illness to thousands from mercury poisoning. I want to share the tragic story of those affected, how the company denied the claims, and the current situation. Just recently, I read a promotional book about the Kumamoto area which branded its craftsmanship, and the place looked lovely, full of mountains and rivers but little did I know about its past and disease. The truth is, I didn't know about Minamata until recently and I believe it's important to share their story. We can all learn from its mistakes and can serve as a lesson for many other countries. Locals and many stakeholders have done great work there, and today it is recognized as the 7th ecological town in Japan.

In fact, Minamata Disease was brought in attention in 2020 from a Hollywood star, Johnny Deep where he plays the role of the American photographer W. Eugene Smith, who was famous for his numerous "photographic essays". The photographer Smith travels to Minamata in Japan to document the devastating effect of mercury poisoning and Minamata disease in coastal communities

While there, Smith becomes the victim of severe reprisals. He is therefore urgently repatriated to the United States. However, this report will make him an icon of photojournalism. Below is the trailer for 'Minamata,' featuring Johnny Depp.

Introduction to Minamata Disease

Minamata Bay is a sheltered area with calm waters, tucked away behind Myojin Cape that sticks out into the Shiranui Sea and Koiji Island offshore. The bay is home to natural features like lagoons and rocky areas where a lot of different fish and shellfish come together, attracted by the pine forests along the shore. It's an ideal place for them to lay their eggs. Minamata Bay is known as one of the top places for marine life to spawn in the Shiranui Sea.

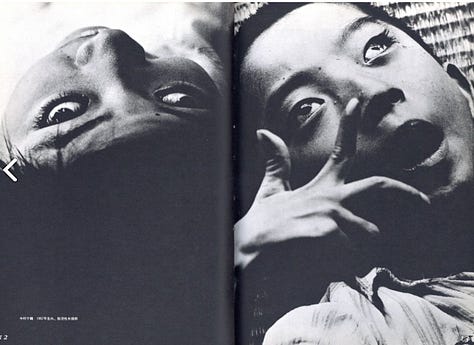

In the mid-1950s, the villagers started to notice their cats behaving strangely—specifically, falling into the sea. Some people even believed the cats had begun to dance, while others thought it was an act of suicide. However, this 'dancing cat fever' wasn't demonic possession. It was a case of environmental poisoning. At the time, people consumed fish that had been contaminated by large quantities of mercury compounds discharged into Minamata Bay by a chemical factory. Minamata Disease is a type of methylmercury poisoning that leads to neurological symptoms. The condition develops after a person consumes heavily contaminated seafood regularly.

Like the cats, some people began acting strangely and shouting uncontrollably. The main symptoms of Minamata Disease include sensory disturbances in the hands and feet, ataxia, balance dysfunction, constriction of the visual field, and hearing loss. The first outbreak of Minamata disease was confirmed in 1956, and the disease was named "Minamata Disease" because it occurred around Minamata Bay in Kumamoto Prefecture. In late April 1956, a 5-year-old girl from Tsukiura with peculiar neurological symptoms was admitted to the Chisso's hospital, which was the most equipped medical facility in the area, followed by her 2-year-old sister with similar symptoms. Their mother reported similar cases in their neighborhood. Suspecting an infectious disease, pediatrician Kaneki Noda consulted with hospital director Hajime Hosokawa. In fact, Director Hosokawa himself had examined two similar patients the previous year, but they died within two to three months without a diagnosis of the cause. Focused on these cases, on May 1, Director Hosokawa and Dr. Noda went to the Minamata Public Health Center to report an outbreak of an unknown disease with neurological symptoms in the Tsukiura area, with four patients hospitalized so far. This date was later recognized as the “official discovery of Minamata disease.”

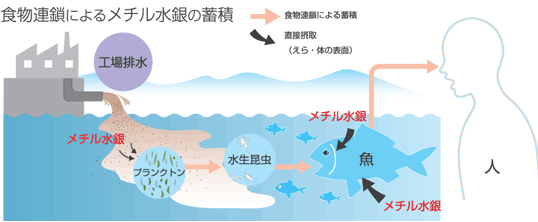

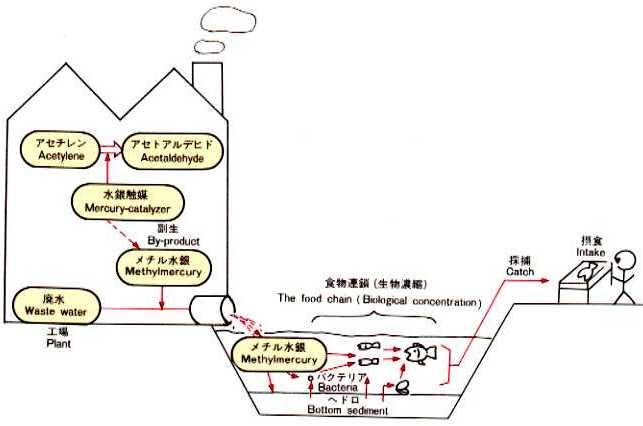

Methylmercury is taken into the body through the food chain, from industrial wastewater to plankton, from plankton to aquatic insects, to the seafood that feeds on them, and finally to humans. There are two types of mercury: inorganic mercury and organic mercury. Methylmercury, which caused Minamata disease, is a form of organic mercury, and even a very small amount can affect the human body. Methylmercury is absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract, circulates through the bloodstream, and is transported to organs throughout the body. In particular, it can pass through the brain's "blood-brain barrier," a defense against toxic substances, and accumulate in the brain, causing damage.

There are two types of treatment for Minamata disease: early treatment and treatment after the symptoms have stabilized and entered the chronic stage. First of all, it is essential to refrain from further consuming seafood with high concentrations of methylmercury, including fish from contaminated areas and larger fish. In acute cases, chelating agents, which bind to mercury and facilitate its excretion in the urine, were used as initial treatment but are no longer in use. For treatment in the chronic phase, vitamin E, which aims to reduce active oxygen within cells, and vitamin B12, which is expected to have a positive effect on the nervous system, are utilized. For cramps, symptomatic treatment is provided using the Chinese herbal medicine Shakuyakukanzoto and medications for spasticity. Because this is a neurological disease caused by a degeneration and demyelination mechanism, rehabilitation in daily life proves to be effective. Reference https://doctorsfile.jp/medication/456/

Who Was Behind This?

In 1906, Chisso's founder, Jun Noguchi, an electrical engineer, established Sogi Electric Co., Ltd. He built a hydroelectric power plant at Sogi Falls in Oguchi Village, Kagoshima Prefecture, and expanded into the Ushio Gold Mine and other locations. Driven by strong local recruitment efforts, Noguchi commenced construction of a carbide manufacturing factory in Minamata Village in March 1907, and by October of the same year, he began power transmission from Sogi Electric. The following year, in August 1908, Sogi Electric and the carbide manufacturing company merged to form Nippon Nitrogen Fertilizer Co., Ltd., which is the forerunner of today's Chisso.

With the construction of the Sogi Power Station in 1906, the horse-drawn carriage drivers who had transported coal, the power source for the gold mine, from Minamata Port were left jobless. In Minamata, where the salt industry had ceased, the primary source of cash income shifted to employment at the Chisso Minamata factory. As Chisso grew, so did Minamata's local economy's reliance on the company. The factory's expansion led to increased wages, attracting workers from surrounding areas. For many, employment at the Chisso factory became a point of pride.

As a result, the population grew in tandem with the development of the Chisso Minamata factory. By 1949, when Minamata achieved city status post-war, there were 8,584 households and 42,137 people. By 1956, the year Minamata disease was officially recognized, the Chisso Minamata factory had an even more significant role in the local economy. According to estimates from Chisso's Minamata Factory Newspaper around 1955, the sum of property taxes, municipal taxes, and other levies paid by the Chisso Minamata Factory and its workers constituted over 50% of the city's tax revenue.

Chisso Corporation made significant advancements by producing improved ammonium sulfate and synthetic ammonium sulfate fertilizers. To support its expanding operations, Chisso built additional power plants across Kyushu and established factories in Yatsushiro and Nobeoka. The company's power generation capabilities grew impressively, from 880 kilowatts per hour in 1908 to about 40,000 kilowatts per hour by 1927, which marked the beginning of ammonia synthesis using the Casale process at their Minamata factory. Initially a fertilizer producer synthesizing ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen, Chisso rapidly evolved into a leading chemical manufacturer, boasting significant technological advancements.

Despite their successes, Chisso was also associated with numerous industrial accidents. Their management's apparent focus on profit, often seemingly at the expense of safety, ultimately led to the environmental disaster known as Minamata disease.

During that period, a major challenge for Japan's chemical industry and the Ministry of International Trade and Industry was the shift from the traditional electrochemical methods to petroleum-based processes. This was a strategic move to enhance Japan's competitiveness on the international stage, especially with the impending liberalization of trade in chemical products. In this context, Chisso's role was pivotal, not only within the economic sphere of Minamata but also within national politics, reflecting its substantial influence and importance.

How Chisso Dealt With It?

Many locals suspected Chisso, the only chemical company in the area, was responsible for the toxic mercury waste. Despite the internal and external fears of confronting Chisso's influence, protests started in 1959 with fishermen demanding the company halt toxic dumping and provide compensation for related illnesses.

Cat experiments inside Chisso in 1957 suggested a link between the company's waste and Minamata disease. Despite clear evidence from these tests, Chisso's management chose not to disclose this information publicly.

On November 30th, Dr. Hosokawa was told to stop all research at Chisso because he was to work with Kumamoto University. But Chisso didn't really help the university's research. They even told the government that their waste couldn't cause Minamata disease. Later, it was found that Chisso's factory waste had dangerous mercury in it, but Chisso had kept that secret. They didn't change how they made things and kept denying that their waste made people sick.

On August 24, 1959, Professor Kiyoura from Tokyo Institute of Technology tested the seawater in Minamata Bay. A few days later, he told the media that mercury pollution in the bay wasn't a serious issue and suggested caution about blaming mercury. In September, Takeharu Oshima, a director of the Japan Chemical Industry Association, suggested that wartime explosives dumped in the bay might be the cause, not mercury from Chisso. But as early as February 1957, researchers from Kumamoto University had already checked and dismissed this explosives theory, and even Chisso had looked into it with no results linking the explosives to the disease.

As the mass media extensively reported on the dismissal of the organic mercury theory by leading experts, the families of Minamata disease patients, who had been negotiating for compensation based on Kumamoto University's support of the theory, lost faith. Uncertain when the true cause would be identified, they felt compelled to accept the consolation payment offered.

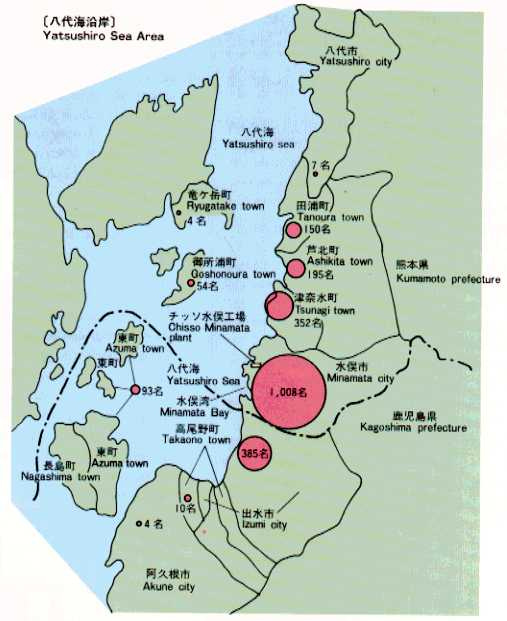

It was eventually determined that the Chisso Corporation had released 82 tons of mercury compounds into Minamata Bay. Continuous mercury pollution over time resulted in congenital cases, where children were born with severe disabilities such as twisted limbs, cognitive impairments, deafness, and blindness due to in utero mercury exposure.

Compensation

Until World War II, Chisso was at the core of a conglomerate known as a zaibatsu. However, after causing Minamata disease, it faced the brink of bankruptcy due to mounting compensation claims from affected patients. In April 2001, the Osaka High Court ruled that the government’s Health and Welfare Ministry should have initiated regulatory actions to prevent the poisoning by the end of 1959, when it was established that Minamata disease was due to mercury contamination. The court also required Chisso to pay $2.18 million in damages to the plaintiffs.

On October 16, 2004, the Supreme Court of Japan mandated that the government compensate Minamata disease victims with 71.5 million yen ($703,000). The Environment Minister offered an apology to the plaintiffs with a bow. After 22 years of litigation, the plaintiffs succeeded in holding those responsible for Japan’s most severe case of industrial pollution accountable for their negligence. In 2010, Chisso was ordered to pay 2.1 million yen and ongoing medical allowances to individuals who were not initially recognized by the government as having the condition.

So what happened to the polluted area?

The contaminated areas of Minamata have undergone significant remediation efforts. Methylmercury that had settled at the bottom of Minamata Bay was addressed by scooping up the mercury-contaminated sediment. Parts of the bay, especially where contamination was severe, were reclaimed. This cleanup operation was completed by 1990. In 1997, a declaration of safety was issued, indicating that the area had been successfully rehabilitated, and the reclaimed land has since been turned into a park.

Additionally, the prefecture conducts annual mercury measurements in the fish from Minamata Bay. These levels are reported to be nearly below the provisional regulatory limits set by the national government. Whitebait and cutlass fish are now marketed as local specialties of Minamata. Minamata City in Kumamoto Prefecture continues to be a hub of industrial activity, with factories that produce essential materials for modern technologies like television and smartphone screens. The workforce in these industries is a significant part of the local employment landscape, suggesting that Minamata has moved beyond its tragic past to a future oriented towards technology and innovation.

In 2011, legislation led to the establishment of a subsidiary to continue the operations of the Chisso factory. This move was part of an effort to maintain compensation payments to those affected by Minamata disease. Even though Chisso could potentially be dissolved, the law ensures that the company's responsibilities to the patients remain in force. Chisso has been responsible for covering hospital expenses and providing compensation to the victims.

As of September 2017, there were 2,282 recognized patients of Minamata disease, of which approximately 1,900 had passed away. Recognition as a patient, which involves certification by the government, is based on specific criteria, including symptoms of the disease. Despite these measures, there are individuals who have experienced symptoms of Minamata disease but have not been officially recognized and certified by the government. These people have reported their grievances and have pursued legal action to seek compensation. As a result of these lawsuits and negotiations, around 70,000 people have received some form of financial compensation. Some cases are still ongoing in the courts.

Additionally, patients of Minamata disease and their families have faced social challenges, including bullying and discrimination. This mistreatment was often rooted in misconceptions about the disease, particularly the unfounded fear that it was contagious, as well as jealousy over the compensation amounts that some patients received. These social issues added to the hardships experienced by those affected by the disease and their loved ones.

Today

During Japan's period of high economic growth, economic growth was prioritized over the environment and human health. Drawing from its Minamata disease experience, Japan now emphasizes environmental care over economic growth, using its past to inform global environmental policies.

Minamata City, once marked by the environmental tragedy of Minamata disease, has since pioneered Japan's environmental initiatives. In 1992, it became the first Japanese city to declare itself an Environmental Model City, setting a precedent for advanced recycling and waste separation practices. The city has implemented its own versions of environmental ISO systems for homes and schools and introduced the Environmental Meister system to drive community-led efforts in reuse, recycling, energy and resource conservation, as well as the development of citizen forests.

These efforts, aimed at combating global warming and environmental degradation, have set Minamata apart as a model for both domestic and international local governments and environmental NPOs. Their approach is particularly noted for being cost-effective and well-suited to smaller local authorities.

Key initiatives include:

A home appliance recycling facility established in 1999, which processes and imports recycled products such as TVs, refrigerators, and washing machines.

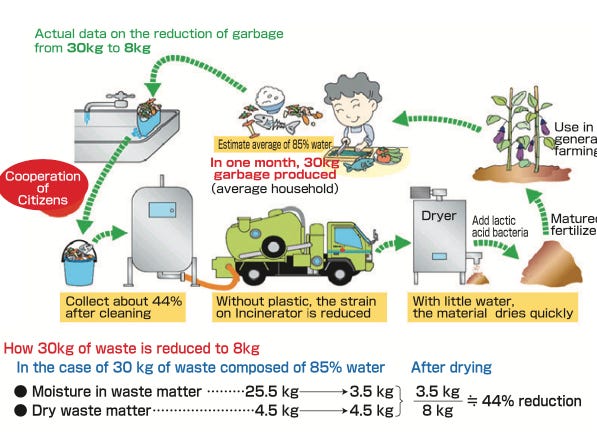

The Environmental General Technology Center, which collects organic waste from homes, restaurants, and factories to produce organic fertilizers using lactic acid bacteria.

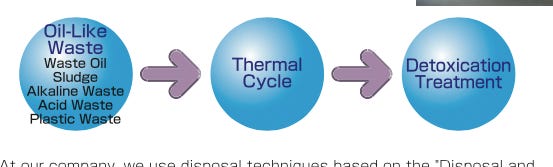

Kiraku Kogyo, a venture that creates heavy oil from the used oils collected and filtered from car repair shops and gas stations.

Reference:

https://www.verywellhealth.com/minamata-disease-2860856

https://www.env.go.jp/en/chemi/hs/minamata2002/ch3.html

https://www.pref.kumamoto.jp/soshiki/47/1707.html

https://www.city.minamata.lg.jp/kankyo/kiji003105/index.html

http://nimd.env.go.jp/syakai/webversion/houkokushov3-1.html

https://www.asahi.com/topics/word/%E6%B0%B4%E4%BF%A3%E7%97%85.html

https://www.city.minamata.lg.jp/kankyo/kiji003105/3_105_21_6515.pdf

https://future-city.go.jp/torikumi/minamata/

http://kumonoue-lib.jp/index.php/kyono-issatsu/447-1-10

https://minamata-impact.com/2021/07/16/nitta-farm/

Sometimes it takes an extreme example of something happening to be able to explain a concept well. Minamata disease is always my go to case study to explain the concept of bio accumulation. Small creatures like krill or bottom feeding creatures end up absorbing small amounts of mercury into their bodies just from being in its presence. Large numbers of these creatures are eaten by larger animals and then even larger animals eat large numbers of those, which leads to everything being passed up the food chain in larger and larger quantities.

Recently I’m finding myself needing to explain the concept of bio accumulation less and less but this is always my go to example. 😁